LEARN WHY AND HOW WE WORKED WITH SYRIAN FAMILIES IN LEBANON

Research Objectives

|

Research Methods

Observation of Daily Life

|

As an ethnographic approach to learning about families’ daily lives, we watched, listened, recorded, and learned about the family from within their homes and communities. In this way, we were able to observe everyday life for Syrian families in Lebanon, paying close attention to where they live, what they do, where they go, learning about their everyday challenges, and how they persevere.

|

Collaborative Family Interview

|

We invited families to participate in a collaborative family interview in the home or another place where the family typically gathers and feels comfortable. The WHOLE family--including children and extended family--was invited to participate in the interview. This allowed for multiple generations to provide different perspectives on the same situation. The stories became rich and multi-layered as different family members add to the family narrative. Conducting interviews within the family’s home gave us the opportunity to learn more about their everyday lives

|

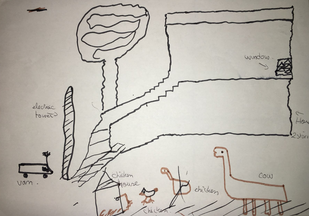

Drawing and Mapmaking

GPS-Tracked Neighborhood Walks

|

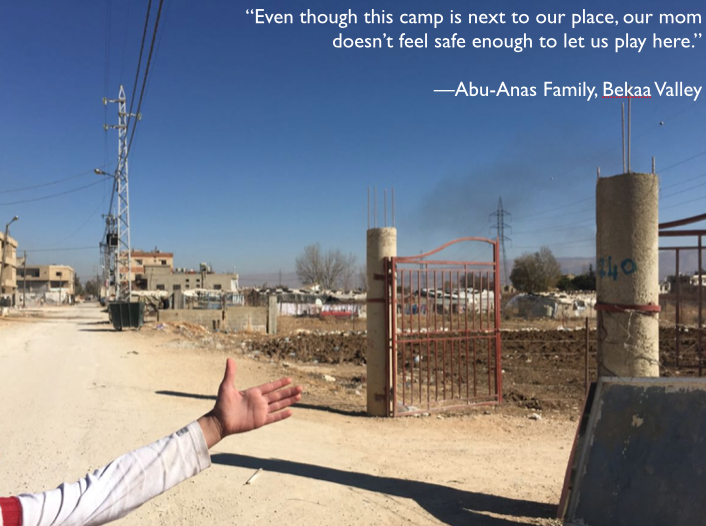

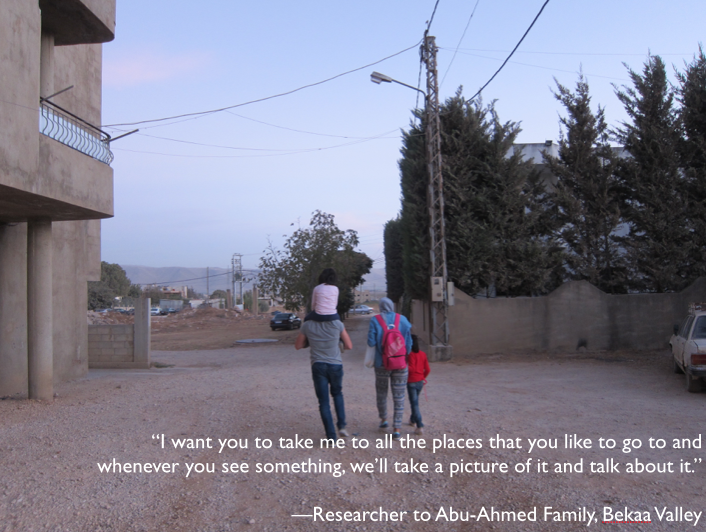

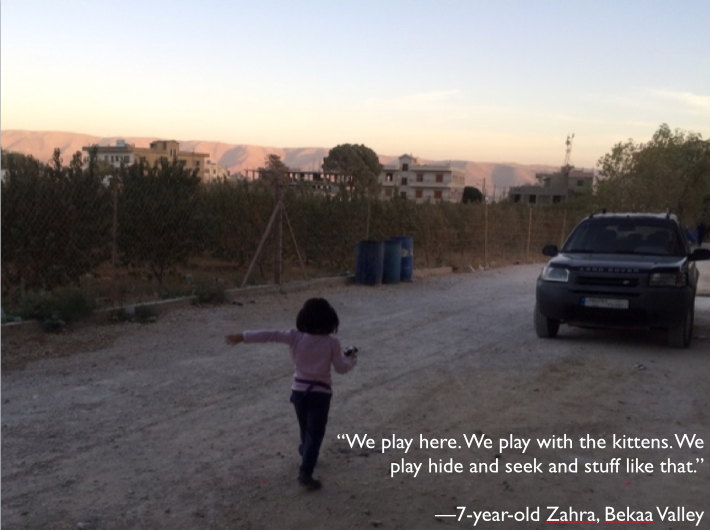

Children were invited to take us on a tour of their neighborhood community. The process of “walking and talking” created a space for dialogue, especially for younger children and girls who may not be given as much of an opportunity to speak during the collaborative family interview. We encouraged children to share the places where they were allowed to visit, where their daily activities occur, and where people they know are located. In addition to observing the children in their natural environments where they expressed their multidimensional place experiences, the GPS technology yielded quantitative data on the length of the neighborhood walk in both distance and time

|

Family Activity Logging

|

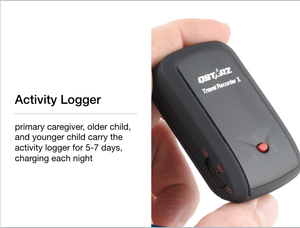

For a period of 5-7 days, the primary caregiver (oftentimes the mother or father), an older child (older than nine years), and a younger children (younger than nine years) were asked to carry a small activity logger for 5-7 days, recording their daily activities and mobility patterns. The family activity logging produced a visual longitudinal record of significant places to correspond with other data from the research. The resulting data was visualized through maps, representing mobility patterns and socio-spatial interactions.

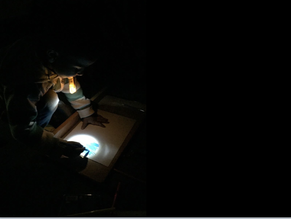

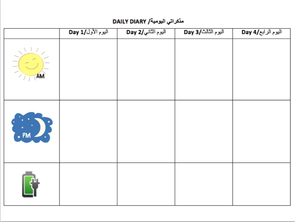

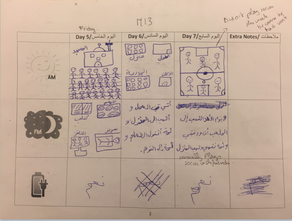

Daily Diaries

To accompany the activity logging, we asked participants to keep a diary of their daily activities (e.g., attending school, shopping for groceries, playing with friends, working, etc.). The daily diaries were used to shed light on the data points collected through the activity loggers.

Follow-Up Interviews

We visited the family after approximately one week to discuss the family's activities and ask any additional questions that were not covered in the earlier collaborative family interview.

Research Analysis

Before we analyzed the data, all interviews were translated and transcribed. Data analysis involved a thorough reading and analysis of family, key informant, and focus group transcripts. Analysis of transcripts was competed using Dedoose, an online platform for mixed methods research. Dedoose allows researchers to highlight and code (or label) sections of the interviews which related to recurring themes that families speak about (e.g. mobility in Lebanon, challenges of life in Lebanon, resiliency & strength). All interviews were read and coded line-by-line. Codes were grouped into four general sections: (1) life in Syria, (2) flight from Syria to Lebanon, (3) life in Lebanon, and (4) hopes for the future.

|

|

Research FAQs

|

What is home?

House implies a built structure, whereas home implies something deeper and more meaningful. In the words of Duyvendak (2011), “a house only becomes a home as meanings and feelings—in other words, a certain symbolic value—are attributed to it. This implies that the material world in itself has no real ‘home value’; for this it needs meanings and feelings to be attached” (p. 37). The concept of "home" is familiar to us all. Yet we all have different interpretations of what home is. Home may be a positive place, providing safety, shelter, and a sense of belonging. But home can also have negative implications. For example, in contexts of family violence, home may provide comfort at some times and violence at other times. No matter what one's relationship with home, it remains at the core of our humanity. Why study home?

Home is a familiar concept for most people. People speak in terms of home all the time. This can be both an advantage and disadvantage in understanding the importance of home in people's lives. Everyone can participate in discussions about the meaning of home, while at the same time, everyone may claim to know the meaning of home and how it feels based on their own personal understandings. These varied understandings of home are what makes home so important to research. The idea of home weaves in and out of the everyday lives of families. Focusing on the home creates more intimate knowledge of the built and the social environment within which the families live. Belonging to a home—and by extension, belonging to a family, community, and nation-state—is part of the process of creating a sense of security and well-being for families, especially those who have been displaced. Are these the actual words of the families?

The families were all Arabic speakers, and so the researchers conducted interviews with families in Arabic. The researchers then translated the audio-recorded interviews into English transcripts, which are what were used for this website and related publications. We have tried to ensure that the words used were identical to the families' actual words. However, there may be some words and phrases that were slightly changed in the process, which is an inevitable part of conducting research in multiple languages. Are those real photos of families' homes and communities?

In order to maintain confidentiality of research participants, we have concealed any photo or mapping data that might lead to identification of the families. Therefore, we have used drawings and modified photos to give you a sense of the place where these families live, while protecting their identities. All families have been given pseudonyms, and we have also slightly changed details about families (such as the Syrian town where they came from) in order to further conceal their identities. What are your next steps?

Our research team is translating the research into both academic publications, as well as more accessible documents such as policy briefs. We hope to impact and inform legislators and community decision-makers through policy recommendations that will contribute to improvements in the conditions of Syrian families living in Lebanon. We’re also trying to educate and mobilize the public by trying to make our findings easy-to-access and interpret. Our future research will focus on the impact of war, displacement, and restricted mobility on parenting, pregnancy, early childhood development, and the family through the lifecourse. |